- The Cautionary

- Posts

- Greed-to-Grief, No. 30

Greed-to-Grief, No. 30

Fake revenue, real prison time

When is a sale a sale? When you buy a pack of gum at a 7-11, money changes hands and you walk out with a product.

Let’s take a more complex example. You have a busy website and sell advertising to other companies that advertise on your site. If your site is a high-traffic weekly newsletter on fraud, bad decision-making, and challenging conventional wisdom for example, you might sell advertising to lawyers or other authors that want to reach your audience.

You charge them based on how many users click on their ad. Pretty simple, and a model that has been around for decades.

But what if you purchased legal services from one of your law-firm advertisers and had an understanding that they really didn’t need to provide you any services but just use the money you paid them to buy advertising in your newsletter. This is called “round-tripping” and is an illegal form of making a sale.

It is not permitted under accounting rules because it is not an honest transaction. Sure, you sold that advertising space and the law firm paid for it. How is this different from the pack of gum at the 7-11? It is different because the law firm never would have purchased the advertising without your funding.

You may ask, “Why would a company engage in such a transaction?” Since money going out equals money coming in, why bother? The one-word answer is: growth.

For most young companies, growth in sales is THE most important metric. Investors assume that when a company is growing, it is taking market share from competitors or creating new market demand for its products or services.

Eventually, the thinking goes, profits will catch up as long as the sales numbers keep rising. New companies in hot markets might grow at 50% to 100% per year.

Growth of 20% annually is considered awesome, especially if it can be sustained year after year.

NVIDIA has grown by more than 100% in each of the last two years, which is extraordinary. Google, which is three times the size of NVIDIA, has averaged about 20% annual growth over the last five years, which is also incredible.

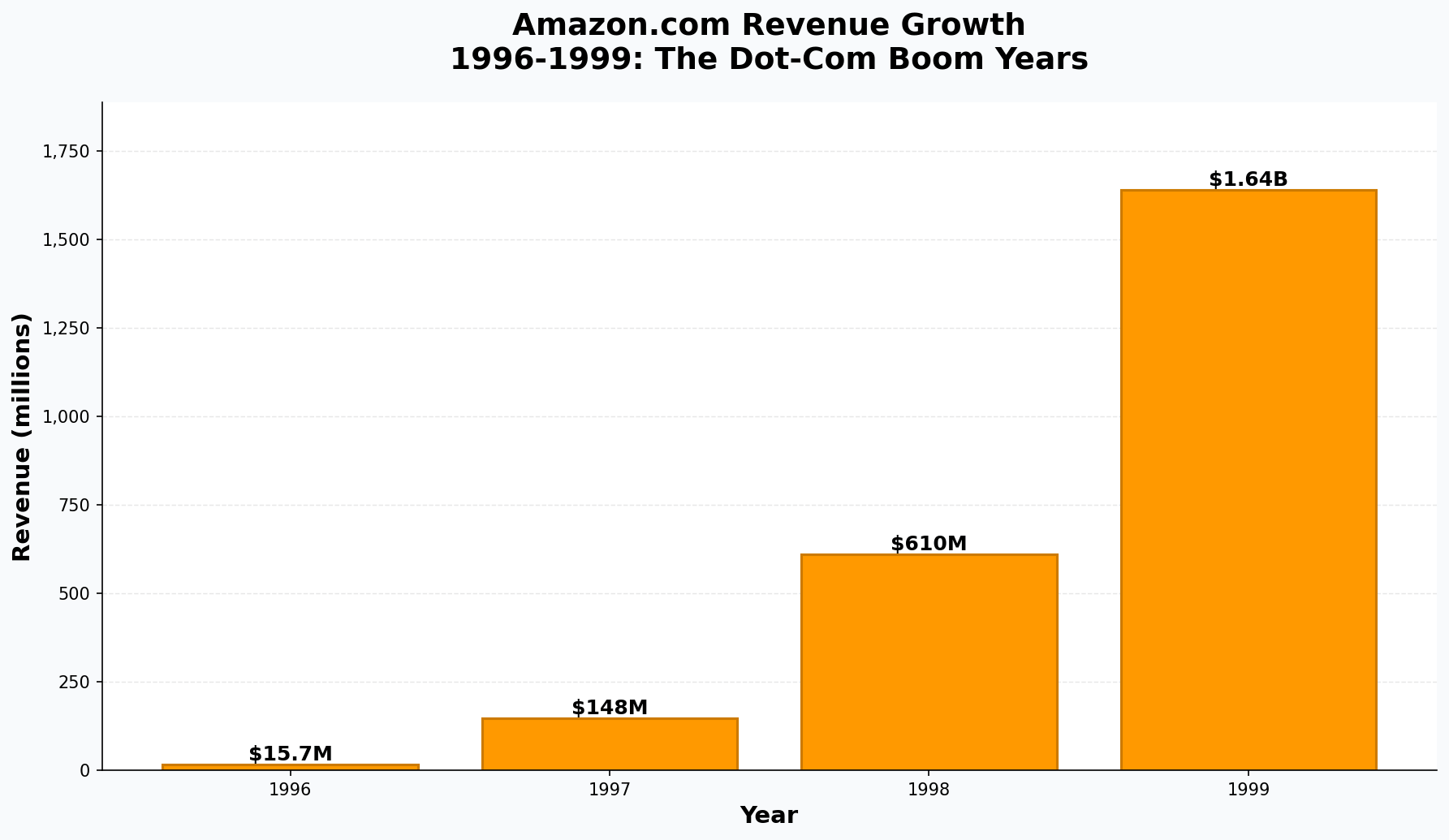

But my favorite example is Amazon. Amazon went public in 1997, a year in which its revenues increased 10x to $150 million. Two years later, the company had revenues of $1.6 billion. The math is mind-boggling.

Companies that show growth are rewarded with increasing stock prices, so who cares about a little round-tripping?

In the case of Homestore.com (the owner of Realtor.com), the SEC and the Department of Justice cared.

Homestore was one of the stocks that took off during the dotcom bubble of 1999 to 2000. Its stock price soared to $140 per share by riding the wave of ever-increasing advertising sales at Homestore.

Since Homestore was attracting the traffic, advertisers were flocking to the site, right? Everybody needs to look at real estate listings and buy houses and Homestore was cornering the market, until it wasn’t.

Homestore started the round trip by sending money to vendors without receiving legitimate services from them. Vendors then buy advertising from advertisers like AOL.com and AOL completes the round trip by purchasing advertising from Homestore. Basically, a form of money laundering.

Driving those sales numbers, which in turn drove the stock price, was a massive conspiracy involving round-tripping of revenue. Homestore worked closely with AOL.com in a scheme where AOL purchased advertising from Homestore in the amount of revenue that Homestore’s “affiliates” purchased from AOL.

Homestore would pay for bogus services from companies with the understanding that those companies would then use the money to buy advertising from AOL. AOL would then “buy” advertising on the Homestore.com website, completing the round trip of the funds.

Princeton Ph.D., Homestore CEO, and convicted felon Stuart Wolff

A sophisticated fraud that involved all Homestore’s senior executives, including its CEO, who had a Ph.D. from Princeton. (These Ivy League schools keep showing up in my stories about fraud. What’s up with this?)

An investigation into the company’s accounting practices uncovered almost $200 million of revenue generated from circular, round-trip transactions. What a mess.

Homestore and its auditor PWC, had to restate a couple of years of financials. (There is almost nothing worse than a restatement, but that is for another post.) The stock went from $140 to $2 per share and twelve officers of Homestore were charged with crimes and sentenced to prison terms.

CEO Stuart Wolff eventually pled guilty to one count of conspiracy to commit securities fraud and was sentenced to four years in prison. I hear they give Ph.D. inmates good jobs in the prison library.

Key Takeaways

Fancy degrees from fancy schools are valuable. But don’t trust somebody just because he or she has one.

The Homestore fraud was a conspiracy that involved a dozen people at the company all who knowingly participated in crimes. Just because everybody is doing it doesn’t make it right.

The company’s board and auditor were asleep on this one. The depth and breadth of the fraud should have been discovered much sooner.

Recommended Reading

Too Big to Fail

Definitive account of the 2008 financial crisis that still reverberates today.

The Subprime AI Crisis

Technology contrarian Ed Zitron summarizing all that AI is not

Run the Storm

Detailed account of the sinking of cargo ship El Faro

The Smartest Guys in the Room

Journalists cover the Enron story end-to-end. The definitive account.

Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder

From the author of The Black Swan. You will learn to think differently after reading this.

Zero to One

Billionaire Peter Thiel on why the bulk of the value is created early in any venture

Full reading list is here.